Warren Buffett has been avoiding -- deferring to be precise -- billions of dollars in taxes by exploiting a loophole in the United States taxation system. However, the taxation systems in Holland and the United States are wildly different when it comes to investments and capital gains. That's why I decided to dive in and compare the effect these two taxation systems have on capital gains to see whether Buffett would prefer to live in Holland, where I live, or rather stay in the States.

I'll start with a brief description of the most important features of both taxation systems and then compare the two using several examples to find an answer to this burning question.

As a citizen of the mighty US of A, you are required to pay taxes on your capital gains. To be precise, you pay taxes over your investment returns and over any dividends you receive. However, the IRS makes a distinction between short-term and long-term capital gains. If you sell your investments within one year, you pay your regular income tax rate. If you sell your investments after one year, lower incomes pay a 10% tax rate while higher incomes pay a 20% tax rate over their long-term capital gains. Dividends are also taxed at your regular income tax rate.

An individual with an average income pays a set dollar amount of $5k plus a 25% income tax over the additional sum. The highest income tax bracket is a fixed dollar amount of $118k plus 39.6% as of 2014.

One funny loophole, which Warren Buffett has been using to his advantage for decades, is that you only pay the IRS once you sell your investments. So as a buy & hold type investor you can keep your tax money invested until you finally decide to sell, whenever that may be. More on this later…

The Dutch Taxation System

In Holland we like, for better or worse, to do everything a bit different. Our capital gains tax is called Vermogensrendementsheffing. Yes. Not an easy word for you non-Dutchies. The Dutch system does not tax actual capital gains, but fictitious capital gains. That's right, fictitious capital gains.

The government assumes you should be able to earn a 4% return on your capital, and they then tax that fictitious return with a 30% rate. So in effect, you pay a 1.2% (4% x 30%) tax on your total capital. It does not matter if you actually made a 0% return or a 35% return, the tax remains 1.2% over the total capital you possessed at the end of the year, minus a tax free amount of €21.139.

Savings are similarly taxed, so if you only get a 2% interest rate on your savings account, you are in fact paying not a 30% tax over this interest, but a 60% tax, since our tax guys assume you would have earned 4% interest at least! Shocking, especially because not many people realize this. In Holland dividends are taxed with a 15% rate.

The average Dutch income is taxed with a 38% income tax, while high incomes are taxed 52%. This may seem like high rates compared to the US system, but keep in mind that in Holland there are no fixed dollar/euro amounts to be paid in addition to this rate.

Holland does not have the beautiful tax loophole Buffett uses, because we pay our Vermogensrendementsheffing every single year, regardless of when we decide to sell our investments. Another curious thing to note is that as soon as your investment returns become your primary source of income, you will no longer pay the 1.2% rate, but instead pay the regular income tax rate over your returns.

Examples

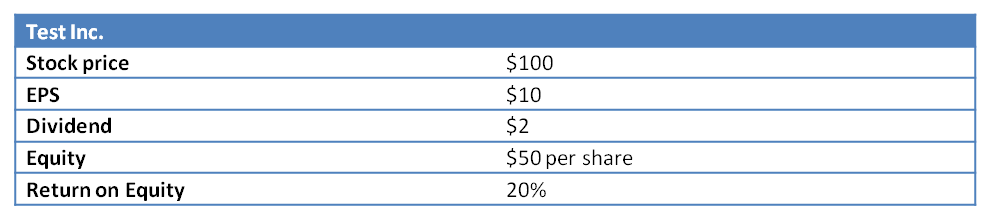

Imagine the following company, Test Inc.:

Table 1 - Financial data for Test Inc.

I mention the Return on Equity (ROE), because this shows how fast a company will be able to grow if it reinvests its earnings back into its business (retained earnings). In this particular case, next year's earnings can be expected to be:

$50 equity per share + ($10 EPS - $2 dividend) x 20% ROE = $11.6

This means a 16% earnings growth rate ($11.6 / $10). Obviously I simplify things a bit here by making the assumption that the company can reinvest all of its retained earnings into cash generating avenues, and does not need to spend anything on R&D or maintenance.

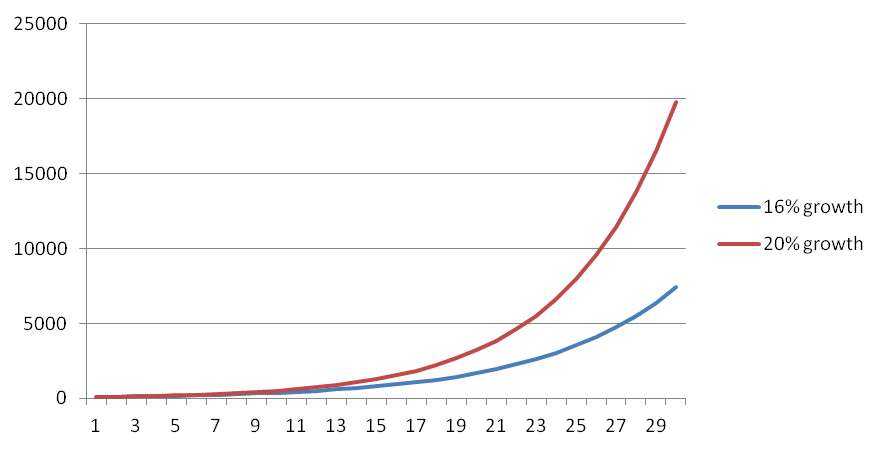

What would happen if the company did not pay out a dividend? Indeed, then the earnings growth rate could have been 20%, which is equal to Test Inc.'s Return on Equity. These couple of percentage points make a huge difference over the long run. That's why Buffett prefers great companies which do not pay a dividend, at least not until their growth prospects have diminished.

Figure 1 - The difference between a $100 investment growing at 16% and 20% a year

Now let us take a look at Warren Buffett, who is most definitely in the highest possible income tax bracket. Buffett is a buy & hold guy for reasons which will become apparent soon.

"Our favorite holding period is forever."

Warren Buffett

Say he owns 100.000 shares of Test Inc. for a total sum of $10 million dollar (100.000 x $100), what would his returns look like if he decides to sell after 30 years, assuming a 16% earnings growth rate and identical valuation?

The value of the stock would have compounded from $100 dollar to an astonishing $8.585 dollar a share ($100 x 1.16^30), a price appreciation of 8585%! His initial $10 million dollar investment would now be worth a whopping $858.5 million dollar.

Buy & Hold versus selling regularly

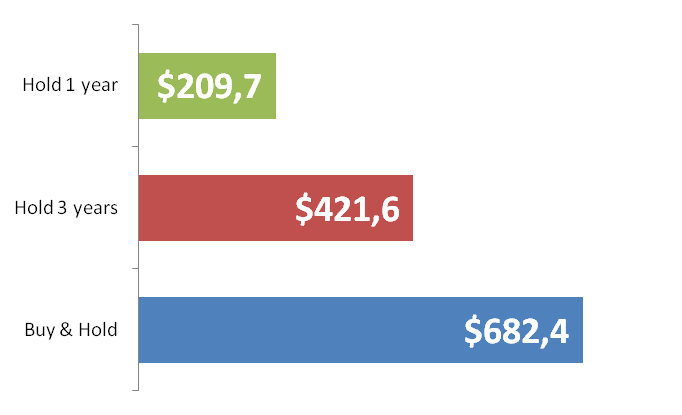

These long-term capital gains are taxed at 20%, resulting in a total net value of $688.8 million dollar ($858.5 x 0.80). Besides that, Buffett would have received $6 million in dividends over those years ($2 x 100.000 shares x 30 years). These dividends would be taxed with the highest bracket, so 39.6%, resulting in net dividends of $3.6 million dollar. In total, Buffett would have earned $682.4 million dollar and paid $172.1 million dollar in taxes. A fair amount.

Now what if Buffett had made one minor change to his strategy: selling his stocks every 3 years and then immediately reinvesting the money instead of selling once after 30 years? In this case Buffett would still have earned the same amount of dividends and paid the same amount of taxes over these dividends, but his total capital gains would be much lower. How much lower? Well, instead of netting $682.4 million dollar, his investments would be worth $421.6 million dollar. Still a good amount of money, but $260.8 MILLION dollar less than if he had only sold once after 30 years!! Buy & hold really pays off…

Things get even worse when we look at what happens to these returns if Buffett would decide to sell his investments within one year, meaning he would have to pay taxes each year and also has to pay a 39.6% short-term tax instead of the 20% long-term capital gains tax. In this unlikely scenario, Buffett's after tax investments would be worth $209.7 million dollar, or $472.7 million dollar less than if he would have sold his investments once after 30 years. This means his total capital gains would be 69% lower by selling his investments within one year versus buy & hold. Remember, the investment and its annual return haven't changed.

Figure 2 - After-tax returns per holding period (in millions $)

These massive differences in absolute returns are for 100% caused by taxation and the disruptive effect taxation has on compounding! By holding on to investments for a long time and only paying taxes at the end of the holding period, Buffett is able to let his tax money work for him. Brilliant!

Dividend vs no dividend

Many people enjoy receiving a steady dividend income, but as we mentioned before, dividends decrease retained earnings and therefore future growth. Of course you could reinvest these dividends, but in our simplified example we simply take these dividend payments at face value. Let's see what Buffett's return would have been if the company had retained and reinvested those earnings, instead of paying them out as a dividend.

As we saw before, reinvesting all earnings back into the company means earnings growth would be 20% a year instead of 16%. If we use this 20% earnings growth instead of the 16% we used before, Buffett would no longer receive a dividend, but the total after-tax value of his 30-year buy & hold strategy would have been $1.9 billion instead of $688.8 million dollar. This is a $1.2 billion dollar difference, just because the dividends were reinvested into the company instead of paid out! This should really make you rethink your desire for a steady stream of dividend payments…

Should you abandon all dividend-paying companies altogether? Absolutely not! Buffett believes dividends are great, but only if it makes business sense. What he means with this is that a company should only pay out a dividend if it has no better use for the cash. If, on the other hand, a company is able to earn a high return on capital, then it should not pay out the cash as a dividend, but instead reinvest it back into the business.

I mean, if you found a company which is capable of earning a 30% return on capital, would you want them to pay you a dividend which first gets taxed and which you then have to reinvest somewhere else, or would you rather let them keep all your money and so it can compound at 30% annually?

I thought so…

American versus Dutch taxation system

So how would Buffett's tax evading buy & hold strategy work if he was a Dutch citizen? Let's move our example from the US to Europe and find out! Since the Dutch taxation system requires investors to pay a 30% annual tax on a fictitious return of 4%, it does not matter if you buy & hold or sell your holdings every year. You pay this 1.2% tax rate regardless.

So at first sight it seems like Buffett might lose his tax advantage if he moves to Holland. However, in Holland he can take advantage of another tax loophole, because Buffett does not earn the 4% that is being taxed, he earns 20% in our example! This means that Buffett does not pay a 30% tax over his capital gains in Holland, but only a mere 6% (a 20% return / 4% that is taxed = 5 times more than is taxed, and 30% / 5 = 6%).

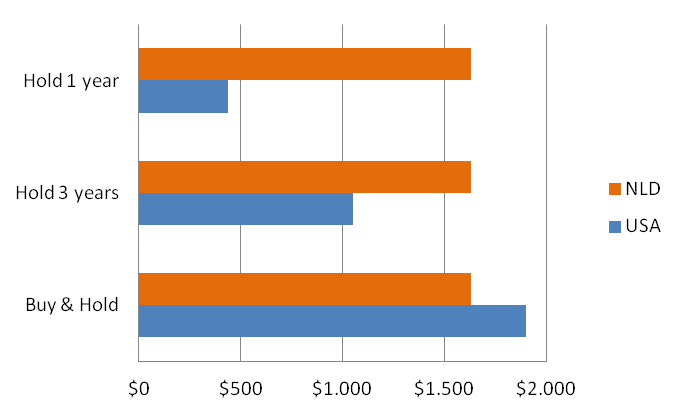

If Buffett invests the same $10 million dollar in Test Inc's stock using a 30-year buy & hold strategy which compounds at 20% a year, the after-tax value of his investment is a whopping $1.6 billion dollar, which is a massive $300 million dollar, or 15.7% less than the $1.9 billion he earned using buy & hold under the US taxation system. So even though Buffett would only pay a 6% annual capital gains tax rate in Holland over his total capital, the American loophole is even bigger. In other words, Buffett would be better off staying in the US (unless he would get an insatiable appetite for stroopwafels or kroketten of course).

However, under the Dutch system it does not matter if you sell your investments regularly or apply a buy & hold strategy; the amount of taxes you pay remain exactly the same. So if we look at more active investment strategies, we see that Holland is a better place to be. If a US citizen again earns 20% annually on a $10 million dollar investment, but would sell her investments every three years, she will be the proud owner of about $1 billion dollar after 30 years. Nice, but this is $600 million dollar less than she would have earned with that same strategy under the Dutch taxation system. For US investors selling their stocks every single year, the difference becomes a staggering $1.2 billion dollar difference!

Figure 3 - After-tax returns per holding period (in millions $) per country

You can download the spreadsheet with which I've calculated these figures here:

Download Tax Calculations Spreadsheet here

The bottom line

What did we learn from this investigation into the effects of different taxation systems on capital gains? Well, several important lessons actually.

First and foremost, many investors, including myself until I wrote this article, severely underestimate the impact of taxes on their ultimate return on investment. However, the examples in this article should have made it clear that in fact taxes play a decisive role and make a huge difference.

Second, if you live in the US, Buy & Hold is definitely the way to go! Simply find a great company which is able to consistently grow its earnings at above-average rates and hold on to it for a looooong time. In Holland you are free to pick whatever time frame suits you best, although shorter holding periods equal more transaction costs of course.

Third, while lush dividend payments might seem enticing at first sight, make sure the company has no better use for the cash than to pay it out, because you saw what a huge difference in total returns these dividend payments can make by reducing retained earnings and therefore future growth.

Again, I simplified things a bit in this article, but the general conclusions are clear. For example, we obviously use Euros instead of Dollars in Holland, and I also did not take transaction costs and some of the finer details of the taxation systems into account, because they would make only a negligible difference as far as I can tell. I'm no taxation expert, I simply looked all of this information up online, so if you spot any mistakes in my calculations, feel free to point them out to me in the comments.

Despite these limitations, I hope you learned a thing or two from this article. I sure did! If you liked this article, feel free to share it by clicking one of the social media buttons below. I would really appreciate it and it motivates me to write more of these in-depth articles.